In 1794, driven by French revolutionary enthusiasm, the students Luigi Zamboni and Giovanni Battista De Rolandis tried in vain to overthrow the secular absolutism of the Church, inciting the people of Bologna to rebel.

The time was not yet right for an insurrection of such magnitude and the two, who were immediately arrested, died because of this bungled and premature attempt, which nevertheless made them the first martyrs of Italian unification.

In 1796, a few weeks after De Rolandis was hanged (Zamboni had died the year before, probably by suicide), Napoleon’s troops entered Bologna and placed the local government in the hands of the jubilant Senate, snatching it from the authority of the papal legate.

The enthusiasm of the aristocrats was also justified by the fact that Bologna had been elevated to capital of the Cispadane Republic. However, it only held this title for a few months, until the Cisalpine Republic was established and the more modern city of Milan was made the capital (July 1797).

As for the Alma Mater, the teaching staff had to swear allegiance to the Constitution of the Italian Republic and those who did not adhere, including Luigi Galvani, Giuseppe Mezzofanti and Clotilde Tambroni, were dismissed from their job.

The secular revolution abolished the teaching of Theology and Canon Law, and transferred the administration of the Studium to the centralised body of the “Dipartimento del Reno”, abrogating the secular students’ guilds of the Universitates and the College of Doctors.

However, it was with the founding of the Italian Republic (1802-05), after the brief period of Austrian rule, that a proper national law on public education was enacted.

Whereas Physics and Mathematics and Medicine were entrusted to the Ministry of Education, the faculty of Law was controlled by the Ministry of the Interior, with the aim of making it standardised and law-abiding. The Rector, chosen from among the professors, was given a sanctioning and coercive role in this.

In 1803, after this radical structural transformation, the University of Bologna was relocated from its historical seat of the Archiginnasio Palace to the less central Palazzo Poggi, which in the previous century had been equipped with laboratories, libraries, offices and lecture rooms provided by the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna.

The latter was closed down and, on the one hand, the National institute for the promotion of scientific activities was set up while, on the other hand, the Academy of Fine Arts was relocated to the nearby convent of Saint Ignatius of Loyola which, like many others in Bologna and throughout Italy, had been abolished by Napoleonic reforms.

The entire north-eastern part was therefore turned into Bologna’s new cultural district, where the Teatro Comunale (Municipal Theatre) had been inaugurated in 1763. The Liceo Filarmonico (later known as the Bologna Conservatory) was opened in the former convent of the Basilica of San Giacomo Maggiore, as well as the National Art Gallery, located in the same building that houses the Academy of Fine Arts, and the botanical and agricultural gardens in the 16th-century Palazzina della Viola.

The shake-up experienced by the University and the city as a whole continued even after the decline of the Kingdom of Italy (1805-14) and in the first decade of the papal Restoration.

The Studium retained its Napoleonic structure, but theological professorships and spiritual exercises were naturally reinstated.

In 1824, a radical reconversion to Catholic ideology took place with the Constitutio qua studiorum methodus of Pope Leo XII, in which the four newly established faculties of Theology, Law, Medicine and Surgery, and Philosophy were required to adhere to religious values, at a time when the rest of Europe was embracing the truths of Positivism.

A Sacred Congregation entirely consisting of cardinals was put in charge of university administration, under which the rectors, who were also clergymen, became vigilant observers of the moral conduct of the academic staff.

The few students who were enrolled during this period, for their part, had to provide a certificate of good conduct signed by their parish priest, and then agree to total control over all aspects of their public and private lives.

Despite this huge departure from reality and contemporary progress, some of the University’s most notable names can also be traced back to those years, such as the jurist Giuseppe Ceneri, the naturalist Camillo Ranzani and, especially, the clinician Francesco Rizzoli, founder of the Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute, which is still one of the most advanced in the world.

There was also a fringe of people who opposed this authoritarian drift, who only managed to impose themselves for a few months through the Carbonari uprisings of 1831. After the brief period of the United Provinces, Rome – having regained its dominion – began to see Bologna and its university as a hotbed for revolutionaries, and with good reason.

When the Roman Republic was proclaimed in 1849, Bologna proudly resisted the descent of the Austrians, who nevertheless managed to recover the papal territories and return them to their rightful lord.

However, the time was ripe for a more organised collective revolution, and the students and professors of the Alma Mater were among its greatest supporters.

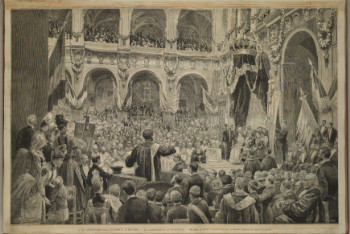

Finally, on 11 March 1860, the people of Bologna, definitively freed from papal rule the year before, voted for annexation to the Kingdom of Savoy.

While rejoicing at the annexation to the Savoy crown, the city reorganised itself in order to prepare for the future, upgrading its buildings and the urban fabric and renewing its ruling class, which would later be involved in the foundation of the Kingdom of Italy.

The Alma Mater, for its part, had to wait almost 30 years to be able to achieve such a change.

Despite establishing new Faculties (Law, Philosophy and Philology, Mathematics, and Medicine), from which that of Theology was excluded, inaugurating the modern university clinics in the former convent of Sant’Orsola (1869), and setting up specialisation schools (Magisterium, 1876; Veterinary Medicine, 1876; Application School for Engineers, 1877; and Political Science, 1883), the entire body could only rely on a few prestigious names. First and foremost among these was the rector Giovanni Capellini, who had the support of some local politicians, such as Marco Minghetti, enabling them to take action to improve the chronically backward state in which the Alma Mater Studiorum still found itself.