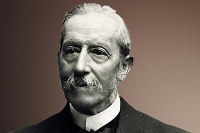

One of the first in Italy to embrace and circulate Darwin’s revolutionary theories, Giovanni Capellini was one of the University of Bologna rectors most attentive to its modernisation and relaunch onto the international scene in the late 19th century. He was behind the plans for the expansion of the university campus and, most importantly, the organisation of the festivities for the 8th Centenary, a ceremony that was indispensable for engineering the return of oldest university in the west to the international stage.

Giovanni Capellini was born in 1833 to a modest family from La Spezia.

Giovanni Capellini was born in 1833 to a modest family from La Spezia.

Not wishing to follow in the footsteps of his musician father, he was originally oriented towards an ecclesiastical career, becoming a prefect at the small seminary of Pontermoli, which was also where he first began to learn about geology, immediately entering into correspondence with specialists in the field.

After his father died in 1854, he was finally able to enrol in the University of Pisa, using funds provided by La Spezia. He studied under Giuseppe Meneghini, director of the Pisa Geology Institute and head of the renowned Tuscan School of Geology, the most advanced of the time.

Graduating in 1858, Capellini decided to travel throughout Italy and abroad to deepen his research and studies. Upon his return, in 1861, he was appointed professor of natural history at the National College of Genoa, where he remained for a very short time.

That same year, the minister of education, Terenzio Mamiani, sent him to Bologna to take the post of professor of geology and direct the geology institute, which he brought international prominence.

The following year, he continued his explorations in North America and eastern Europe, always staying up-to-date on what was happening in his field, new developments in which were filling the scientific literature at the time. As noted above, he was one of the first to study and circulate Darwin’s theories.

The renown that the University of Bologna had achieved thanks to Capellini and other distinguished professors, all of whom called by Minister Mamiani, was such that the 5th International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology was held in Bologna.

The need to create a transnational community in his own field led Capellini to found the International Geology Congress, the second meeting of which, in 1881, was held at the freshly reinvigorated University of Bologna. The event was an astonishing success and led to the formation of the Italian Geology Society (1881), headed by Capellini with the assistance of Quintino Sella and Felice Giordano. It was a real triumph for the Ligurian scientist, cemented by the opening that same year of the geology museum that still today bears his name. The museum was formed around the old geological and palaeontological collections of Aldrovandi, Cospi, Marsili and Monti, previously kept at the Istituto delle Scienze and now considerably expanded by the post-Italian-Unification finds that were immediately provided by Capellini upon his arrival in Bologna.

But the geologist’s best year was 1888.

Capellini had already served as rector from 1874 to 1876, and when he took up the post again in 1885 he had the opportunity to put together a special committee (that included his friend Giosue Carducci) for the grand relaunch of the University of Bologna through the celebration of its 8th Centenary. Taking inspiration from the festivities organised at other, far younger, European universities, the committee decided to promote the historical school by reasserting its status as the first and deciding, more or less arbitrarily, the date of its founding: 1088. Italy was still trying to find the common ground for its path to unification and Bologna opted to present itself as the city of the crenellated town hall and the mother of universities. With few funds but all of the enthusiasm brought by an exciting, positive period (the new railway station was completed in 1876, the Giardini Margherita opened in 1879 and then hosted the Grande Esposizione in 1888), the event brought not just the University of Bologna back into the fore, but also the whole city, which, in the presence of Umberto I and Margaret of Savory, listened to Carducci’s solemn speech in the courtyard of the Archiginnasio.

That same year, Capellini, together with the engineer Giovanni Barbiani, was working on the plan for the university campus, which was part of the city’s more complex first town plan (1886-89) and located the old institution’s science buildings along the new via Irnerio.

From 1889 to 1912, Capellini, now quite advanced in years, held a post inherited from his tutelary deity, Meneghini, that of president of the Italian Geological Society, which had been working since 1861 on the Italian geological map, of both scientific and political importance for the nascent nation.

During this long period of directorships and other top posts, he served as senator in the seventeenth legislature (1890) and was once again elected rector (1894-95), while in 1907 he devoted himself to completing one of his most important contributions to the university: the re-establishment of the Museo Aldrovandi. After the celebration of the third centenary of the death of the illustrious Renaissance scientist, the collection reorganised by Capellini became the starting point for the museumisation of the scientific materials given by the Istituto delle Scienze to the university in the early 19th century, which, after being broken up and dispersed, have now been partially reunited and brought back to Palazzo Poggi.