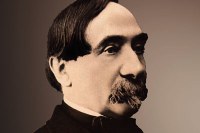

Wherever he went, he rose to the top as director or administrator. Young and penniless, Francesco Rizzoli moved from Milan to Bologna and built a career worthy of his times, the period when physicians and surgeons raised their rank to the highest echelons of society. Solitary and frugal, Rizzoli was tirelessly committed to the social and scientific improvement of his profession, making an immense contribution to the formation of modern orthopaedics and financing an orthopaedic institute in Bologna that remains one of the best in the world.

Francesco Rizzoli was born in Milan in 1809 to a family of humble origins.

Francesco Rizzoli was born in Milan in 1809 to a family of humble origins.

His father, a lieutenant in Gioacchino Murat’s army, was killed by brigands, and young Francesco, still a child, had to move with his sister Teresa to his paternal uncle’s home in Bologna.

In spite of the precarious economic conditions which led him to be almost obsessively frugal his entire life, the young man managed to take a degree in medicine, in 1829, and one in surgery, in 1831.

Immediately after, and in part through the support of his brother-in-law, the physician Paolo Baroni, he began to work intensely in the hospital and academic spheres.

In 1834, he became assistant to the chair of obstetrics and theoretical surgery (held by Baroni), becoming full professor in 1840, while in the meantime having begun, in 1835, to work at the Pio ospedale del Ss. Salvatore, where he served as department head until 1855.

For the city’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, which he became a member of in 1842, he taught midwives obstetrics, a discipline that had made its debut in university teaching in Bologna between the 18th and 19th centuries, thanks to Giovanni Antonio Galli and, most importantly, Maria dalle Donne. Rizzoli’s main contribution to the discipline was his invention of the hooked forceps.

The 19th century was marked by an enormous jump in the social status of physicians, who inevitably often ended up holding high public and political posts. This was the case for Rizzoli, who was called in 1848 to join Bologna’s public health committee and the following year he was even elected deputy of the nascent National Assembly of the Roman Republic, although the post did not last for long, since the pope was soon back in control of the territories he had briefly lost during the First Italian War of Independence.

In 1851, he was appointed substitute professor of clinical surgery, and then promoted to full professor in 1855, the same year in which he took over as head of the university’s surgery ward, which was located at the time in the Ospedale Azzolini (also known as the Ospedale della Maddalena), near the university.

In 1852, he became president of Bologna’s Society of Physicians and Surgeons, holding the post until his death.

Before leaving his post as department head at the Pio ospedale del Ss. Salvatore, he had had the opportunity to demonstrate his managerial aptitude and skill through his decision to accommodate the overflow of cholera patients during the 1855 epidemic in specially provided structures at his hospital (for which he was elevated to the rank of Bolognese nobility).

The hospital that he was about to take charge of now, Azzolini, immediately presented him with logistical and hygiene problems, having been built at the end of the 17th century and only partially modernised by Angelo Venturoli in 1808, when it became the Ospedale per le Cliniche medico-chirurgiche universitarie.

In the meantime, he continued his public and political rise as a progressive, first (in 1859) as deputy of the Assemblea delle Romagne and then, following Italian Unity, as provincial advisor, a post that he held until 1880.

The arrival of the Savoys gave him the opportunity to become consulting physician to the Royal House (1860) and to work with other doctors to cure Garibaldi’s wound and save his leg from amputation (1862).

In spite of his important scientific and executive contributions (he had also become head of the city hospitals) and the fame he had achieved, Rizzoli was bitterly opposed by the minister of public education who, weary of his endless complaints about the Azzolini hospital, decided to pension him off, removing him from teaching in 1865.

This did not prevent Rizzoli from offering his services to the new Ospedale Maggiore, which, in 1857, had gathered together the central and antiquated Ospedali della Vita e della Morte and numerous religious medical structures into a more modern, decentralised healthcare system and immediately offered Rizzoli the post of head of surgery, which he held until 1876.

Rigorous and stern, Rizzoli refused to return to teaching when the university granted him the title of professor emeritus in 1868 (he also refused the professorship offered to him by the University of Pavia in 1876), finally conceding that he was right about the Ospedale Azzolini, which was permanently closed the following year, once the clinics joined the ones already established at the Ospedale di S. Orsola, which is still a university polyclinic today.

Rizzoli’s decades of experience in healthcare and city politics spurred him to sit on the Cassarini town council, which was, in 1870, working out a democratic system of public education and an innovative home medical service, which Rizzoli was unfortunately never able to see, since it was instituted the year after he died (1881).

He continued to collect institutional posts even in the final years of his life, becoming president of the Accademia delle Scienze in 1871 and a member of numerous other international societies and academies.

Although rich and famous, he maintained the self-restraint of a man devoted to his profession, unmarried and frugal, accumulating an enormous fortune and collection of properties. In his palazzo in Strada Maggiore, the ancient via Emilia, he even hosted Giosue Carducci, his humanistic counterpart in the university liberation of the second half of the 19th century.

Like Ulise Aldrovandi, Francesco Rizzoli joined the large University of Bologna family of distinguished individuals who bequeathed gifts and legacies to the city and the university. In 1879, the surgeon, by this point near death, bought the former monastery of San Michele in Bosco, with the intention of transforming it into a sophisticated orthopaedic facility as a gift to the province.

During his lifetime, orthopaedics had grown considerably in importance and he was renowned for his fast, meticulous operations, at a time when sterilisation and anaesthetics were in their nascent stage (he was one of the first to use chloroform, in 1847, however, maintaining that the reactions of the patient were useful during operations but not being able to bear the screams, he patented an earmuff, which is now preserved in the Libreria Umberto I).

Thanks to Rizzoli, this branch of medicine, which had been anticipated by Hippocrates but not reintroduced into university teaching until the 1740s, now had a new, specialised hospital system, attentive to hospitalisation and rehabilitation. And so, the isolated complex of San Michele in Bosco, which was inaugurated in 1896 as the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli, immediately became an international leader in the areas of orthopaedic surgery and traumatology, and is still supported today by the university’s research and faculty.

The old surgeon had by this point achieved such importance and prestige that he received the royal appointment of senator of the 8th Legislature, although he was unable to complete his term, dying the following year, to the entire city’s grief.

Francesco Rizzoli’s funeral was held in the basilica of San Petronio, with numerous authorities in attendance, and it was immediately decided to name one of the city’s main streets after him. Running between Due Torri and Piazza Maggiore, it was, at the time, still part of the highly trafficked Mercato di Mezzo, but soon (1910) modernised as part of a town plan that gutted the old quarter for reasons of hygiene, itself the cornerstone of the new age and the key to the brilliance of the surgeon and philanthropist’s career.