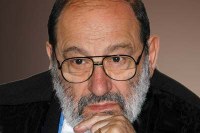

The University of Bologna showered Umberto Eco with all of the titles and awards at its disposal, grateful to the renowned semiologist for having enriched it with his teaching and the courses that he created and made famous.

Umberto Eco was born in Alessandria in 1932. The grandson of a typographer and son of a railway employee, he was immediately drawn to the world of reading and the cult of the book.

Umberto Eco was born in Alessandria in 1932. The grandson of a typographer and son of a railway employee, he was immediately drawn to the world of reading and the cult of the book.

After completing his classical education at the secondary school in his hometown, he enrolled in the Faculty of Literature and Philosophy at the University of Turin, graduating in 1954 with a thesis on the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas, which was responsible, as Eco himself wrote ironically some time later, for having miraculously healed him of his faith (he revised his thesis in 1956, turning it into his first book: Il problema estetico in San Tommaso).

After graduating, he went to work at Rai along with other brilliant young intellectuals, forming a mixed and revolutionary group dubbed the “corsairs” and thanks to which the television programme schedule was brought up to date and acquired fame as a true public service.

The following year, he began fruitful and important collaboration with the nascent magazine “L’Espresso”, writing the popular, ironic weekly cultural column La bustina di Minerva from 1985 to 2016. He also contributed to numerous other newspapers, including “Il Giorno”, “La Stampa”, “Il Corriere della Sera”, “La Repubblica”, and “Il Manifesto”, as well as myriad international specialist journals.

In the meantime, he deepened his interest in semiotics and linguistics, in part in connection with the communicative laboratory that was television (his celebrated article Fenomenologia di Mike Buongiorno was published in 1961).

In 1959, he was offered a prestigious editorship at the Bompiani publishing house, a post that he held, achieving notable results, until 1975. His editorial choices were heavily influenced by the avant-garde movement Gruppo 63, which was supported in turn by the thinking of the young intellectual, who was critical of writers still tied to the outdated literary criteria of the 1950s.

In 1961, Eco began his long university career, first in Turin, then in Milan and Florence, transmitting to his students his reflections on mass media and their influence on mass culture, some of which came together in Diario minimo in 1963 and Apocalittici e integrati in 1964. His series of talks held in New York in 1967, Towards a Semiological Guerrilla Warfare, was a major success, and later reworked into the volume Il costume di casa (1973), a benchmark text on twentieth-century counterculture.

His publications on semiotics and literary criticism continued to follow close on each other’s heels, soon bringing Eco into the international limelight as a leading expert in the field (here one might mention the talks that he gave between the 1990s and the first years of the 21st century at Cambridge, Harvard, Toronto, Oxford and Emory). In 1968, he published La struttura assente, in 1971, Le forme del contenuto, in 1973, Il segno and Beato di Liebana, in 1975 the Trattato di semiotica generale, the following year, Il superuomo di massa, in 1977, Dalla periferia all’impero and Come si fa una tesi di laurea and, finally, in 1979, Lector in fabula.

In 1971, he had already founded “Versus – Quaderni di studi semiotici”, continuing to serve as editor and remaining on the scientific committee until his death, and meanwhile became secretary and then vice-president of the IASS/AIS ("International Association for Semiotic Studies"), becoming honorary president in 1994.

When DAMS (Discipline delle Arti della Musica e dello Spettacolo) was founded in Bologna in 1971, Eco was among the very first to flock to the revolutionary degree course, created by Benedetto Marzullo to consider the various performing arts in their new social context through the innovative combination of traditional teaching and activities like seminars and workshops. In 1975, Eco was appointed to the Semiotics chair at the University of Bologna, and then headed the Istituto di Discipline della Comunicazione e dello Spettacolo in 1976-77 and 1980-83.

This was the period of his rise to global fame with the publication of Il nome della rosa (English translation: The Name of the Rose, 1983), winner of the 1980 Strega Prize and an instant bestseller translated into more than forty-five languages: a gripping hybrid novel, part historical thriller, part narrative and philosophical text, made even more famous by its film adaptation in 1986.

In 1988, his second long-awaited novel came out, Il pendolo di Foucault (English translation: Foucault’s Pendulum, 1989), which, although it sold even more copies than the first, never achieved the same level of success.

The 1980s were also the period of Sette anni di desiderio (1983), Semiotica e filosofia del linguaggio (1984), a collection of articles written for the Enciclopedia Einaudi, Sugli specchi e altri saggi (1985), Arte e bellezza nell’estetica medievale (1987), Lo strano caso della Hanau 1609 (1989), and the translation of Raymond Queneau’s Esercizi di stile.

In the 1990s, he published: I limiti dell’interpretazione (1990), Stelle e stellette e Vocali (1991), Il secondo diario minimo, Interpretation and overinterpretation (1992), La ricerca della lingua perfetta nella cultura europea (published in 1993 in Jacques Le Goff’s Making of Europe series), Sei passeggiate nei boschi narrativi, Cinque scritti morali and Kant e l’ornitorinco (1997), Tra menzogna e ironia (1998), just to cite a few.

His third novel was published in 1994: L’isola del giorno prima (English translation: The Island of the Day Before, 1995).

In the meantime, a new degree course was organised at Bologna, separate and distinct from DAMS, and in 1993, the department of Communication Science was inaugurated with a ceremony in the new Aula Magna di Santa Lucia, with Eco as its head. Hundreds of young people from all over Italy flocked to the university to take the admissions exam for the new degree programme.

The planning of new courses of study then led the famous semiotician to found and head the Scuola Superiore di Studi Umanistici in 2000, and then, the following year, the Master in Editoria cartacea e Digitale, both set up in Palazzo Marchesini in via Marsala 26.

In the final years of his life, by this point living in Milan Eco often found a pretext for returning to Bologna, whether for a talk or a bit of research, always welcomed by students with admiration. The very conformation of the city had become familiar to him, almost a propagation of his thinking, a dense synaptic fabric and fluid labyrinth of arcades, where people meet and exchange information.

The first decade of the twenty-first century was filled with an endless series of varied writings, including La bustina di Minerva (2000) Sulla letteratura (2002), Bellezza. Storia di un’idea dell’Occidente (2002), Dire quasi la stessa cosa (2003), A passo di gambero (2006), Storia della bruttezza (2007), Dall’albero al labirinto (2007), Non sperate di liberarvi dei libri (2009), Vertigine della lista (2009), Costruire il nemico e altri scritti occasionali (2011) and Sulle spalle dei giganti (2017), as well as his last four novels: Baudolino (2000), La misteriosa fiamma della regina Loana (2004), Il cimitero di Praga (2010) and Numero zero (2015).

This immense life’s production was for the most part published by Bompiani, the publishing house where Eco also met his companions for a new publishing adventure, La nave di Teseo, the publishing house that he founded in 2015 with Elisabetta Sgarbi, Mario Andreose and Eugenio Lio.

Not only printed paper, articles, essays and novels, but also an important contribution to the emerging technological world, which Umberto Eco had anticipated, predicting the future needs and directions of modern society and developing a well-reasoned, distinct critical sense of the new horizons for mass culture that would soon be generated and transmitted through the internet and social media. The resulting verdict led him to see and support the positive sides of that new world, which is still germinating today and is, on the other hand, also predisposed by its very nature to give “legions of idiots the right to speak”. A democratic globalisation through new technologies was possible in part thanks to data controlled and offered freely by platforms like Wikipedia, which he had also anticipated in the multidisciplinary project Encyclomedia: a collection of essays on the history of European civilisation.

A global man, therefore, interested in every form of knowledge, from the reflexiveness of St Thomas to the ”Allegria!” of Mike Buongiorno; a man who won the esteem of the world, receiving no fewer than 40 honorary degrees, including from Brown University, the Sorbonne, the University of Moscow and the University of Jerusalem.

Retiring from teaching in 2007, the University of Bologna granted him the title of professor emeritus the following year and, in 2015, the Sigillum Magnum, grateful to him for his lectures and innovative methods of research and teaching.

When Umberto Eco died in 2016, the whole city of Bologna and its university celebrated him as one of their own, dedicating the covered Piazza della Sala Borsa, the social and cultural heart of the old town, to him.

Finally, in 2021, after years of negotiations, Eco’s modern library (44,000 volumes) and archive were given to the University of Bologna, which will preserve them, organised as per the intellectual’s request, in a special space next to the university library.

Eco’s teaching will thus continue in the spaces that he used for more than thirty years.

Video L'Alma Mater, perché?