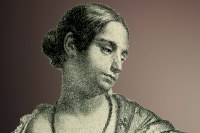

The University of Bologna’s first female doctor of medicine, Maria Dalle Donne was born the same year that Laura Bassi died. She thus took her place as exceptional graduate and teacher, to be celebrated because a woman, but also kept to one side, as an extra. She headed the School of Obstetrics for forty years, teaching modern midwives with professionalism and rigour, while the midwives themselves were seeing their ancient profession elevated to the status of a medical discipline, rendering it therefore “necessary” for male doctors to take charge.

Maria Nanni was born in the Bologna Apennines in 1778 to a humble peasant family.

Maria Nanni was born in the Bologna Apennines in 1778 to a humble peasant family.

Due to a malformed shoulder, she was unable to work in the fields and was entrusted to the care of her paternal cousin, a priest and teacher of medicine, Giacomo Dalle Donne, later taking his surname.

As we read in a letter written in 1789, he immediately noted the young girl’s gifts, writing

“I have an eleven-year-old girl with me from Bologna who speaks and writes Latin and studies humanities. We can place all our hopes in her becoming a new Laura Bassi,”

and he introduced her to the physician and botanist Luigi Rodati, who taught her the arts and sciences.

When Rodati became professor of legal medicine and pathology in 1792, he brought Maria with him to Bologna, where she was taught by numerous professors at the university: the mathematician Sebastiano Canterzani taught her philosophy, Giovanni Aldini Fisica and Gaetano Uttini taught her anatomy and pathology, and Tarsizio Riviera taught her obstetrics.

The latter discipline had first become a part of academic teaching in Bologna itself, when, in 1757, the Istituto delle Scienze appointed, first, Giovanni Antonio Galli and, then, Luigi Galvani to direct the new experimental course.

Numerous instruments and sophisticated models that were used to teach obstetrics to both medical students and midwives can be seen today in the museum in Palazzo Poggi, a building that was first the seat of the Istituto and then became that of the university. For reasons of “decorum”, the student midwives entered through a side door and were taught the basic rules, while they watched their art, passed down from woman to woman over millennia, transform into a medical subject that was soon controlled by the male hospital hegemony.

Riviera’s aim was not, however, for Maria to become a simple midwife, but, more ambitiously, for her to become a physician.

And so, in August 1799, the young woman demonstrated her erudition in a long public defence held in the church of San Domenico, after which she would be permitted to sit the exam for her degree on 19 December that same year. She was accompanied to the event, which had captured the interest of the whole city, by Clotilde Tambroni, professor of Greek language and literature, and the two entered the anatomical theatre of the Archiginnasio together, before the admiring eyes of colleagues and the numerous women who had flocked there for the occasion. Maria demonstrated her perfect mastery of numerous branches of the subject through her two dissertations, highlighting a special interest in obstetrics and pointing out her up-to-date knowledge of themes that had not yet received much attention, such as placenta circulation and foetal malformations.

Dalle Donne then earned her teaching license, in May 1800. The twenty-two-year-old again defended two dissertations in the church of San Domenico and the third and final dissertation at the Archiginnasio, with special attention paid to female health during pregnancy and the circulation of blood in the uterus.

On 31 May 1800, Maria Dalle Donne was admitted to the Accademia dei Benedettini as an extra member, like Laura Bassi fifty-five years earlier.

As had been the case for her illustrious predecessor, Maria was celebrated by the university as a woman and as an international asset while also having to fight to have the academic status she had achieved rewarded with a real job.

For this, she had to wait until 1804 but, whereas Bassi had managed to secure an internal teaching post, Dalle Donne had to settle for an external appointment as director of the new School of Obstetrics.

She held this position for nearly forty years, and for most of that time she had to host the young midwives and hold her courses in her own home. Right from the beginning, she fully understood the care that needed to be taken in selecting students and the necessity of adopting a severe, diligent manner, acutely aware of the difficulties inherent to the profession and the risks involved, especially in the smaller villages, located far from hospital support.

On the other hand, she is documented to have been attentive to the needs of the young women, especially those from less affluent families, who she provided with generous economic support, mindful and appreciative of the help she herself had received.

In addition to the pension from the Accademia dei Benedettini, she was supported by the philanthropist Prospero Ranuzzi, who provided her with an annual income and a valuable collection of scientific instruments.

When her friend Clotilde Tambroni gave the inaugural speech for academic year 1805/1806, she lauded Maria as the latest in a series of learned women and female professors and as the promise of the further expansion of spaces for women within the university. Unfortunately, the times were quickly changing and, with the Napoleonic reformations, followed by the papal restoration, the extraordinary climate of 18th-century Bologna was abruptly brought to an end, and it was not until the end of the 19th century that the university would start to see the slow return of female students and professors.