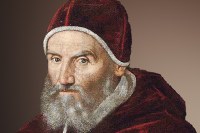

In troubled, revolutionary times, when Christian Europe was crumbling, the Turkish “enemy” was still at the gates and the Americas were opening up a new vision of the world, the Church of Rome placed itself in the hands of the Bolognese Ugo Boncompagni, professor of Canon Law at the University of Bologna. Becoming Gregory XIII, the jurist pope was deft at concentrating administrative power in his own hands, surrounding himself with charismatic figures including Carlo Borromeo and Gabriele Paleotti, and delegating the Jesuits with the spread of a new-found Catholic spirituality.

Ugo Boncompagni was born in Bologna in 1501 to Cristoforo Boncompagni and Angela Marescalchi, both members of wealthy merchant families.

Ugo Boncompagni was born in Bologna in 1501 to Cristoforo Boncompagni and Angela Marescalchi, both members of wealthy merchant families.

In 1530, he graduated in utroque jure, which is to say Roman and Canon law. It was an especially happy year in Bologna, with the city hosting the coronation of Charles V by Clement VII.

Boncompagni taught Law at the city’s university from 1531 to 1539, teaching, among others, Alessandro Farnese, Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, Reginald Pole, Stanislaus Hosius and Paolo Baruli d’Arezzo.

When he finished teaching in 1539, he began his long ecclesiastic career.

Moving to Rome, he was appointed second collateral judge of the Campidoglio in 1540, one of the two judges of the civil court, becoming a priest two years later and, finally, referendario utrisque signature in 1545.

Appreciated for his knowledge of law, he was involved in the Council of Trent, which was temporarily moved to Bologna in March 1547.

When the two Emilian sessions closed, Boncompagni returned to Rome (1548) as a Council jurist, with the arduous task of defending the translation opposed by the emperor Charles V.

That same year, his father died and left Ugo a sizeable inheritance, including part of the family’s beautiful palazzo in Bologna, which was useful to him later for receiving guests as a cardinal.

Also in 1548, Ugo became a father, his son Giacomo born to an unmarried woman named Maddalena Fulchini.

With the rise to the papal throne of Julius III (1550), his previous duties were not renewed for the second phase of the Council (1551-52), but he was appointed papal secretary.

Paul IV, however, returned him to the council circuit (1556), also having him accompany his nephew Carlo Carafa on his international missions in France and to Brussels and appointing him in 1558 to the commission charged with legitimising the resignation of Charles I and the rise to the imperial throne of his brother Ferdinand I.

Also under Paul IV, Boncompagni was appointed vice-regent of the Apostolic Camera and became a member of the newly formed State Council in 1559, that same year being given the bishopric of Vieste by Pius IV.

Attached to his new papal family, he returned to playing a decisive role in the Council of Trent, which opened in 1562 and closed in late 1563.

Back in Rome, he was employed by the cardinal nephew Carlo Borromeo, who helped him to obtain the coveted cardinalship in 1565. As cardinal, he was sent as legate a latere to Spain in connection with the Inquisition’s long-standing accusations against the archbishop of Toledo, Bartolomé de Carranza, who was protected by Philip II. This sensitive mission ended upon the death of the pope and all accusations were dropped. Boncompagni was there long enough, however, to win the praise and admiration of the Spanish king.

Back in Rome, under the new pope, the unbending Pius V, he was removed from government responsibilities so that he could fulfil his duties at the Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura from closer at hand.

These same skills, which had often earned him a hand in ecclesiastic legal matters, were his pass to Peter’s throne in 1572. After a conclave lasting just two days, Ugo Boncompagni became Gregory XIII.

By comparison to his predecessors, he limited the number of posts given to relatives. He appointed Filippo Boncompagni only formally as head of papal policy, a post actually given to the cardinal Tolomeo Gallio, he named Cristoforo Guastavillani governor of Ancona and archbishop of Ravenna and gave a cardinalship to Filippo Guastavillani, the villa of whom in the Bologna hills is now home to the University of Bologna’s Business School.

As for his son Giacomo, he was quite generous with his meddling, appointing him keeper of Castel Sant’Angelo and gonfalonier general of the Holy Roman Church, the highest military post of the Papal States, also giving him the marquisate of Vignola, purchased from the Este, and the duchy of Sora, in the Kingdom of Naples.

Gallio was the only one to whom he granted full powers, concentrating the management on the government in his own hands, with a centralised vision of the administration ushered in by Pius IV.

His papal goals likewise remained those of his predecessors: Catholic Reform, the struggle against the Protestant Reform and the clash with the Ottoman Empire, which had been beaten but not wiped out the year before his election, in the glorious Battle of Lepanto (1571).

One can say, nevertheless, that, while in the case of the latter two goals his successes were quite feeble, in that of the former, the internal reform of the Church, Gregory XIII was an expert executor.

He still believed in the mission against the Turks, but the old papal allies were by then absorbed by internal worries: the Empire and France owing to the Protestants, Spain the colonisation of the Americas and Venice the mainland retreat.

In France, the pope was looking apprehensively at the submissive behaviour of Charles IX and his mother Catherine de’ Medici with regard to the Huguenots and was bitterly surprised when Henry III, albeit briefly, liberalised the religion (1576), trying in the end to rectify the disasters of the Valois, close to extinction, by participating in the formation of a Catholic alliance between the Bourbons and the Guise.

On the English front, he was hoping for the removal of Elizabeth I, initially working towards a marriage between Francis of Valois and the Spanish infanta and then accepting the plan of Philip II to concentrate everything on Mary Stuart and arrange her marriage the brother of the king of Spain, Juan de Austria. The latter, however becoming governor of the Netherlands, removed himself from England’s designs to deal with the anti-Hapsburg rebellions, these, too, poorly handled by Gregory XIII.

As for the Empire, neither Maximilian II nor Rudolph II came to the pope’s aid, neither against the Turks nor against the Protestants.

Whereas Gregory XIII unexpectedly found an ally on both fronts in the voivode of Transylvania Stephen Báthory, who then also became king of Poland in 1575.

Relations were no better with the king of Sweden, John III Vasa, who, although married to a Catholic, Catherine Jagiellon of Poland, was unable to fully assert his authority over the Protestant nobility.

In Italy, Gregory XIII’s policy was subtle but decisive, as we can imagine even just looking at his Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace (1580-85), a project that he entrusted to the Dominican friar Ignazio Danti: an Italy fragmented but reunited in his apartments.

From the religious point of view, on the other hand, the Bolognese pope systematically applied the decrees of the Council of Trent, which boosted the centrality of Rome.

By comparison to Pius V, he was less rigid in his relations with the European rulers and their local governors, since his goal was cohesion more than religious control.

In 1573, he immediately implemented the Congregation of Bishops instituted the year before by Pius V and increased the number and importance of nuncios. The mission of the reformed Church abruptly veered from the attempt, by that point considered empty, to bring Europe back under a single cross to the universal goal of converting the world’s populations. In order to create new adherents to this mission, fully indoctrinated into the Tridentine precepts, the focus needed to be on widespread diffusion of modern seminaries, often entrusted to the teaching order of Jesuits. The followers of Ignatius of Loyola thus became the pope’s most powerful weapon, not only within the Church, but also in the missions in the Americas and Asia (one of Gregory XIII’s last decrees, in 1585, was to give the Jesuits exclusive rights to evangelisation in China and Japan).

Having lost hope in bringing the Protestant countries back to Catholicism, Gregory invested heavily in establishing a new dialogue with the Eastern Churches – Syrian, Coptic, Abyssinian and Armenian – in a vain attempt at reconciliation with the Orthodox church, as well.

The Jesuits, by that point in full control of the new doctrine, were rewarded by the pope with the elevation of their Roman College, founded in 1551 by Loyola, to Archiginnasio Gregoriano, which is still known today, in honour of Boncompagni, as the Pontificia Università Gregoriana.

They were not the only ones to benefit from the pope’s systematic policy: the new orders of the Barnabites, Theatines, and Capuchins were also protected and favoured, as were the Discalced Carmelites, reformed by Teresa of Ávila, and the Oratorians, only recently founded by Filippo Neri. These hosts of humble monastic servants transformed into a powerful cultural machine that was reorganising the Church for a new spiritual and penitential role.

Numerous other expedients were deployed to reunite Catholicism and restore its centralised, uniform management.

First among them the publication, in 1582, of the Corpus Iuris Canonici, the juridical pillar of the Roman Church until 1917 and based on the Decretum, which had been compiled and written by Gratian and his Bologna School in the twelfth century.

That same year, the cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, now also metropolitan archbishop of Bologna, published his Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane (Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images), establishing a new artistic approach that was both simple and effective and especially useful for captivating and moving the masses of believers.

The cult of images, rejected by the Protestants, was broadly elevated by the Roman Church, including through the systematic study of the catacombs and their early Christian paintings.

Standardisation also obviously came through censure. As soon as he was elected pope, Gregory XIII implemented the decision of Pius V to establish a permanent Sacred Congregation of the Index of Forbidden Books. He continued to rely on the Holy Office of the Inquisition, founded by Paul III in 1542, having a list drawn up in 1577 of twenty cases that would trigger excommunication.

To elevate Catholic truth and tie it to the Roman Church, he was always opposed to translation of the Holy Scripture. He entrusted Carlo Sigonio (who been his student in Bologna) with the writing of a History of the Church (never finished), in response to those written by the Protestant doctors in Magdeburg. Lastly, he commissioned a precise Roman Martyrology from Cesare Baronio, from whom Filippo Neri had already asked for an Annales ecclesiastici: the result was two primers that extol the saints, blesseds and martyrs, linking them to specific new feast days.

The latter were inserted into the new calendar that still bears the name of the Bolognese pope today: the Gregorian calendar.

The recalculation of the passage of time had been driven by pure religious need. Over the centuries, the gap between the civil year and the solar year had grown to ten days and this had shifted the date of the spring equinox, which determines the date for Easter, to 11 March. And so a special committee was set up, presided over by the bishop of Sora, Tomaso Giglio, who was succeeded by the cardinal Sirleto in 1576, and formed by theologians, jurists and scientists. Of special importance to the committee was the above mentioned Ignazio Danti, professor of Mathematics in Bologna at the time, who Gregory XIII entrusted with the design of the astronomical Tower of the Winds, specifically for the precise definition of the new calendar.

The committee wrote up a Compendium, which, after being verified by various professors at Catholic universities, came into force on 24 February 1582, the year in which, with the papal bull ‘Inter gravissimas’, Thursday 4 October was followed by Friday 15 October.

Throughout his long papacy, Ugo Boncompagni always maintained excellent relations with Bologna and its university, both of which were indispensable to him in the reform of the Church. For the 1575 Jubilee, he had the Vatican banquet hall frescoed with a large, highly detailed map, so that all of his guests could admire his hometown. In response, the city dedicated a bronze statue to him, cast in 1580 by Alessandro Menganti, which still stands, benedictory, above the entrance to the Palazzo del Comunale today.