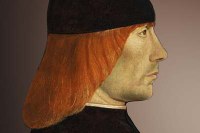

Commonly described as the “commentator of the Bolognese Renaissance”, Filippo Beroaldo the Elder knew better than anyone else how to make the most of the spirited, varied culture that characterised Bologna under the leadership of Giovanni II Bentivoglio.

Filippo Beroaldo was born to a noble family from Bologna in 1453. Thanks to the far-sightedness of his mother, Giovanna Casto (his father died when he was just four), the young Filippo had the opportunity to study in a city open to the dizzying array of cultures that were circulating in Italy and abroad at the time.

Filippo Beroaldo was born to a noble family from Bologna in 1453. Thanks to the far-sightedness of his mother, Giovanna Casto (his father died when he was just four), the young Filippo had the opportunity to study in a city open to the dizzying array of cultures that were circulating in Italy and abroad at the time.

Thanks to a brief period under Cardinal Bessarion (1450-55), Bologna had retaken its place on the world stage, vastly enriching the options for study at the University. The Byzantine east, as well as Islamic scientific culture, filtered into all of the disciplines, soon reinvigorated by the invention of printing.

Beroaldo’s teacher was indeed Francesco Dal Pozzo, who had founded Bologna’s first printery in 1470.

Upon completing his studies, the promising humanist became professor of rhetoric and poetry (1472), departing shortly after for a long trip that took him first to Parma (1476) then, probably, Milan, and then to Paris (1476-77), where he taught at the university for about a year, winning fame as an Italian intellectual, circulating Petrarchism and Ficino’s Neoplatonism.

The University of Bologna tried to call him back multiple times, but had to wait until 1479 before he agreed, as one might expect of the free and independent personality that we read of in his biographies.

The local political situation deteriorated soon after, following the Malvezzi’s ill-considered conspiracy against the Bentivoglio family (1488). The latter withdrew into a form of defensive government, expelling the enemy families from the Senate and launching a massive propaganda campaign, using both the arts and the university, packed with courtiers in their pay.

Beroaldo was among them. Elected an Elder in 1489, he also received important appointments including ambassador and public orator (he wrote the oration for the wedding of Annibale Bentivoglio and Lucrezia d’Este and a political panegyric in praise of Ludovico il Moro).

The learned courtier continued to teach and tirelessly devote himself to writing commentary on the works of classical authors, although he later received harsh criticism for his unscientific approach to ancient texts. Nevertheless, his new editions of no fewer than twenty-four Latin authors rekindled European interest in the various ancient literary forms, including those that had been until then discredited. This was the case for the novel of Apuleius, which could only have been resurrected in a goliardic but refined environment like that of Bologna. The moralising and Christological interpretation of the fable of Cupid and Psyche, told in the Golden Ass, was a major success, in particular in the visual arts (examples include Raphael and Giulio Romano), thanks to him.

Besides the Latin authors, he was also interested in modern writers (he translated Petrarch’s Vergine bella and three novellas by Boccaccio into Latin) and he wrote countless speeches and short treatises on themes popular at the time (happiness, vice, luck, wisdom, etc.), to the point that his friend Giovanni Pico della Mirandola nicknamed him the “living library”.

But he was also the subject of harsh criticism for his depraved lifestyle, which only quieted down in 1498, when he married at 45 years of age. His wife was Camilla, daughter of his distinguished colleague, the jurist Vincenzo Paleotti.

In 1502, he and three other university professors were called upon to exhort the population to defend the city, under threat from the terrible Cesare Borgia.

The dream was about to end, but death came before he could awaken.

Giovanni II managed to hold out against Valentino, but not against the new pope Julius II, who succeeded in entering the city in 1506, putting an end to the long period of Bentivoglio independence.

Beroaldo, an exemplary representative of that period, had died the year before, in 1505.

Humanism stepped aside for the high Renaissance, and the eclectic, at times capricious, culture of the philology professor was not understood by his successors.

While visiting Bologna, Erasmus lamented that he had not been able to meet the famous scholar, but he did not skimp, as was also the case for Paolo Giovio, on severe criticism of his methods and the results of his studies.

Beroaldo was to remain a happy interlude in an age by then outmoded.