Pasolini had a very close relationship with Bologna during his secondary school and university years. The University of Bologna remained impressed upon his work thanks to the lectures given by his art history professor, Roberto Longhi, from whom he absorbed a profound visual culture.

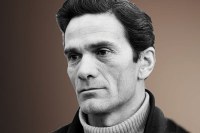

Pier Paolo Pasolini was born in Bologna, in via Borgonuovo, in 1922. His father, Carlo Alberto, was a military officer and belonged to the cadet branch of an aristocratic family from Ravenna, while his mother, Susanna Colussi, was an elementary school teacher.

Pier Paolo Pasolini was born in Bologna, in via Borgonuovo, in 1922. His father, Carlo Alberto, was a military officer and belonged to the cadet branch of an aristocratic family from Ravenna, while his mother, Susanna Colussi, was an elementary school teacher.

His father’s military career meant that Pasolini’s childhood was marked by continuous moves from one city to the next in northern Italy. He attended grammar school in Reggio Emilia and the Galvani secondary school in Bologna, where the Pasolini family returned in 1937.

Skipping his final year of secondary school, Pero Paolo enrolled in the department of Literature in 1939, where he became friends with Roberto Roversi and Francesco Leonetti and reconnected with his friend from grammar school Luciano Serra.

Fascinated by his lectures – the course Fatti di Masolino e Masaccio” was to be incisive for his career – he decided to ask Roberto Longhi to supervise his degree thesis.

His attraction to archaic and primordial expressions in art led to his publication of Poesie a Casarsa in 1942, a short book in Friulian dialect (his mother was from Casarsa). It was a period of experimentation for Pasolini, perceiving himself as a pure pioneer, a free, uncorrupted eternal adolescent. As for his intellectual development in Bologna, Pasolini contributed to the monthly of the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, “L’Architrave”, and co-founded the magazine “Il Setaccio”.

His intense relationship with Friulian rural culture was broken up by the war, with the twenty-year-old Pasolini Paolo called to arms just days before the armistice (1943). The experience had a profound influence on the young writer, who was taken prisoner by the Germans along with his unit. He managed to escape, taking refuge in Casarsa, where he joined his family. During his daring escape, however, Pasolini lost the notes for his degree thesis and, once he returned to Bologna, he decided to change topic and so also supervisor, graduating in 1945 with a thesis on Giovanni Pascoli, supervised by Carlo Calcaterra.

While his father was in Africa, first as a combatant in the Italian colonies, then as a prisoner of war in Kenya, Pasolini taught at a small private school that he opened with his mother and, later, at a middle school in Valvasone, in the province of Pordenone.

He was devastated by the death of his beloved brother Guido, killed in 1945 by Garibaldian partisans, who were hoping for Friuli’s allegiance with Tito’s Yugoslavia.

In 1947, Pasolini became a member of the PCI (Italian Communist Party), working actively not only in the political field but also the literary one.

His initial inclination towards lyric poetry and autobiography yielded to a project for a novel dealing with social issues that was first to be titled La meglio gioventù, but was published much later, cut down and radically reworked, in 1962, as Il sogno di una cosa. This novel already included the theme of homosexual eroticism, reflecting the writer’s interest in young farmers, who he often met at local festivals and fairs. One of his countless sexual encounters was found out and caused a stir, bringing Pasolini one step from a conviction (1949). This episode had inevitable consequences, including his suspension from the school and expulsion from the PCI.

Pasolini and his mother decided to leave the town where the scandal had taken place, taking refuge in Rome in 1950, at the home of a materal aunt (he father fell into depression after the episode and was to join them later).

The move to the capital inaugurated a period of grace for Pasolini, who managed to free himself from ostentatiously pious provincialism in the 1950s (his novel on the theme, Il disprezzo della provincia, was published posthumously) and enter into contact with artists and intellectuals like Sandro Penna, Giorgio Caproni, Moravia and Elsa Morante. He was immediately fascinated by the local underclass and its poverty-stricken beauty.

He first attempted an acting career at Cinecittà, and then went back to teaching from 1951 to 1953 at a school in Ciampino.

As luck would have it, his neighbours were the Bertolucci, with whom Pasolini immediate struck up a friendship. He took his first steps in film making with Bernardo, while his father Attilio secured him a commission from the Guanda publishing house for two anthologies, on of twentieth-century dialect poetry and the other on popular Italian poetry.

In 1954, he worked as a screenwriter for Mario Soldati’s film “La donna del fiume”, and then worked with Federico Fellini on “Le notti di Cabiria” (1957) and “La dolce vita” (1960).

In the meantime, he continued to write, publishing his Friulian poems in the volume La meglio gioventù in 1954, and, the following year, the controversial novel Ragazzi di vita. In 1957, he published the poetry collection Le ceneri di Gramsci (which made him unpopular with the communists for his criticism of the PCI leadership) and then, in 1959, the ideological novel Una vita violenta.

In 1955, he began contributing to the bimonthly poetry magazine “Officina”, which was founded in Bologna by his old friend Roberto Roversi.

Pasolini’s escape into the working class world, far from bourgeois respectability, understood as a cultural disease more than a position in society, was not enough when, in the 1960s, with globalisation champing at the bit, even the most destitute were coming into line with the single way of thinking of the West. New and farther distant horizons were opening up as a remedy to the disorientation: the Third World countries were becoming promised lands where geographic remoteness coincided with the purity of a primitive lifestyle.

His only refuge in a Rome that he no longer recognised became Ninetto Davoli, the only one of the countless kids from the working-class suburb who had made a stable life for himself.

Proletariat or middle class, young people had by this point lost their salvific and revolutionary mission, which we can still catch sight of in the 1965 feature-length documentary “Comizi d’amore” (his interviews of a few students at the University of Bologna are of special interest). Despondency and total delusion took over after his trip to the United States in 1966, as reflected in his critical analysis of the student protests in Italy in 1968: the standardisation of transgression had brought the revolutionary cause to adhesion to a new form of classism and so to a kind of entirely bourgeois civil war.

Loss of hope and certainty led Pasolini to explore new paths in literature, as much through poetry collections, like the angry La religione del mio tempo (1961), the non-representational Poesia in forma di Rosa (1964) and the neurotic Trasumanar e organizzar (1970), as in unfinished novels and meta-narratives, like La divina mimesis (1963) and Ali dagli occhi azzurri (1965).

But it was through film that Pasolini was able to free himself from the shackles of fiction and make deeper, more stinging contact with the public. Accattone (1961), Mamma Roma (1962), La Ricotta (1963), Uccellacci e uccellini (1965), Edipo re – partly set in Bologna, under the Portico di Servi and in Piazza Maggiore – (1967) and Medea (1969), marked and disrupted the history of Italian and indeed world cinema.

From the purity of his first years to the escape during his youth and the criticism received in adulthood, Pasolini had reached a state of despair in his last years. And indeed, the 1970s began with his abandonment by the actor Ninetto (1971).

His work with the ‘Corriere della Sera’ alternated with that in film and literature.

Testaments to his life and reflections on the society that had deluded and distanced him still stand today as key aspects of Italian culture: the banned film Salòo o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (part of which was film in Bologna in the open space in front of Villa Aldini), the collection of Friulian poetry la Nuova gioventù and the unfinished novel Petrolio.

When he was fifty-three, Pasolini was found dead near a field in Ostia (1975). A scandal-ridden, counter-current life thus came to an end. A sex-based line of investigation was immediately opened, with the accused Pino Pelosi convicted “in collusion with unknown others” as the murderer in revenge for a few young men or their protectors. Only recently, another, more unsettling and complex line of investigation opened up, that of Eugeniio Cefis, former president of ENI and president of Montedison at the time, who it though may have been the principal, based on what Pasolini revealed in his novel Petrolio (unfinished when he died), which is to say the truth about the plane crash that killed Enrico Mattei.