Made to study law by his father, Bologna was the obvious choice for Petrarch’s studies. In the letters written when he was in old age, he always remembered that period of his youth with mixed affection and melancholy, a time spent wandering carefree through the city, all the way up to its hills, enjoying the pleasures of Bologna, a city that he described as not only intellectual, but “fat”.

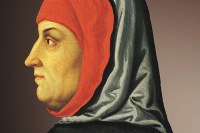

Petrarch was born in Arezzo in 1304 to Florentine parents, White Guelphs who had been forced in exiled two years earlier.

Petrarch was born in Arezzo in 1304 to Florentine parents, White Guelphs who had been forced in exiled two years earlier.

In 1312, Petrarch’s father was hired as a notary at the papal court, which had recently moved to Avignon. The family thus moved to Carpentras, where Petrarch was tutored by the man of letters Convenevole da Prato.

In 1316, the young Petrarch was sent to study in Montpelier, continuing his law studies in 1320 in the more prestigious Bologna. There, he began to discover his true leanings and started studying under and forming friendships with the scholars at the Università degli Artisti, including Giovanni del Virgilio and Bartolino Benincasa. During the chaotic period when the University of Bologna revolted against the municipality for having executed a Spanish student guilty of abducting a young local woman (1321), Petrarch returned to Avignon, resuming his studies in Bologna the following year. This was likely the period during which he began to write poetry in the vulgate, following in the footsteps of Guido Guinizzelli and imitating the local troubadours, with whom he had enjoyed his adolescence under Bologna’s arcades and in the surrounding hills.

We moved from Montpelier to Bologna, and I do not think that one could find a more beautiful or more free place in all the world. You will surely recall the crowd of students, the order, the vigilance, the dignity of the professors, who looked so much like ancient jurists.

…

And then the fertility of the land and abundance of all things, earning the city the nickname Bologna the Fat.

…

At once both sweet and bitter, as you are well aware, it is for me to recall, amidst all these miseries, that happy time, when (and, as with me with you as well, the memory shall always remain indelible and vivid) I was a student there. Already an adolescent and bolder than I had been before, I went around with my contemporaries and on holidays we would walk for pleasure so far from the city that we would often return in the dark of night. Even the gates were wide open, and if by chance they happened to be closed, it was no bother at all, because there were no walls, just a fragile barrier, already split apart by age, encircled the safe city, so peaceful that there was no need for any kind of wall or stronger barrier.

(Letters of Old Age, 10.2)

In 1325, he asked his father for a considerable sum of money to pay for large number of books he had purchased from the Bolognese bookseller Bonfigliolo Zambeccari. This was the beginning of what became the most remarkable private library of the 14th century.

The young scholar’s interest in classical texts led him to work out an innovative approach to the manuscripts in circulation at the time. Petrarch was inventing the discipline of philology, a process involving stripping a text of its medieval allegorical readings and searching for an exemplar as close as possible to the original. One of the best results of this painstaking work was the Ambrosian Virgil, which he began in his youth (in about 1324) and continued to revise, annotate and expand over the course of his long life.

It was only upon his father’s death, in 1326, that he could fully satisfy his passion for literature and the humanistic disciplines. Indeed, Petrarch left Bologna and abandoned his study of law that very same year.

Without his father and the prestigious profession he had been training to join, it became critical for him to find a protector who would offer him “comforts” for the courtly otium that, after him, became essential for future intellectuals. Petrarch found the support he sought in the Colonna family, a member of Europe’s cultural, political and religious elite.

As he recalled in the Secretum, it was while back in Avignon that he first met Laura (1327).

In 1333, he decided to take vows (without, however, respecting the vow of celibacy), beginning his passionate support for the return of the papacy to Rome the following year, with the election of Benedict XII. Exasperated by the French curia, loathe to return to Italy and tangled up in various less-than spiritual affairs, he decided to move to the nearby village of Valchiusa, where he could create his own literary coterie and begin writing what were to be many of his Latin masterpieces, like the epic poem Africa, the biographical anthology De viris illustribus and the collection Epistolae metricae.

His fame at the European courts and universities, thanks to the Colonna family, and at the spirited Angevin court in Naples, thanks to the Augustinian monk Dionigi, led to the fulfilment of his greatest wish: to be crowned in Rome with the laurel wreath of the ancient poets (1341).

In the meantime, Petrarch had also devoted himself to the vulgate, beginning what would become a milestone of Italian literature, the Canzoniere in 1336: a collection of 366 poems that he revised no fewer than nine times over the course of his life.

The 1340s were marked by a series of deaths that plunged the poet laureate into meditation on the fragility of the human condition. When Laura fell victim to the plague in 1348, this feeling became even more acute.

In 1346, Petrarch was named canon of the cathedral of Parma, becoming its archdeacon two years later. During the plague, he found refuge in Verona, where he happened upon Cicero’s epistles, which immediately became the model for his own Familiares.

In the meantime, the political career of his friend Cola di Rienzo, who he had met in Avignon in 1342, came to an abrupt end. The Roman tribune had encountered an insurmountable obstacle to the project to bring back ancient Rome, which had been passionately encouraged by Petrarch. In 1347, Cola was taken hostage by Petrarch’s own protectors, the Colonna family, and in response he decided to withdraw from their support.

These were, however, extraordinarily fruitful years, in spite of the difficulties. Petrarch began the anecdotal Rerum memorandarum (1343), the religious treatise De vita solitaria (1346/53-66), the “Virgilian” Bucolicum carmen (1346-58), the three dialogues of the Secretum (1347-53), the treatise De otio religioso (1347-57), the allegorical De remediis (1347-56) and the spiritual Psalmi penitentiales (1347).

At the end of the decade, he finally managed to find a new patron, in the person of Jacopo II da Carrara, who offered him the canonry of the cathedral of Padua in 1349.

On his way to Rome for the Jubilee of 1350, he stopped in Florence, where he met Giovanni Boccaccio. The two developed a relationship founded on sincere friendship and mutual admiration, and Petrarch gained much from the writer of the Decameron, who introduced him to ancient Greek and classical philosophies that had been previously neglected.

In addition to studying Greek, he also refined his skills in Italian during that period, writing the short allegorical poem Triumphi (1351) in the new literary language.

In the early 1350s, Petrarch rejected numerous prestigious posts, including a professorship at the University of Florence and even an appointment as papal secretary to the new pope Innocent VI, choosing instead to remain permanently in Italy.

Accepting an invitation from the archbishop of Milan, Giovanni Visconti, he began, in 1353, a long, stimulating period in the service of that Milanese family, earning himself bitter criticism from his Florentine friends.

Besides seeing to various errands in various parts of Europe, Petrarch was also able to continue working on projects already begun and start new ones, including the epistolary collection Seniles and the dialogues gathered under the title De remediis utriusque fortune. His need to guide humanity towards ethical and moral principles filtered through Augustinian Neoplatonism and Christian Stoicism became increasingly urgent.

In 1361, he was forced to leave Milan, which was overwhelmed by the plague, stopping first in Padua and then Venice, where he remained until 1368.

Venice welcomed him with great ceremony, asking for the promise of his vast library in exchange. But when four Averroists accused him of ignorance, his hosts failed to defend him (he did this himself, writing the Neoplatonic treatise De ipsius et multorum ignorantia), and so Petrarch decided to leave the lagoon, bringing his books with him.

He moved to nearby Padua, where Francesco I da Carrara had offered him protection and the canonry in 1368. The final years of the ‘supreme poet’ were tranquil, spent in his home in Arquà in the Euganean Hills, where, cared for by his daughter Francesca, he was able to revise his works for the last time.

Petrarch died in 1374, on the day before his seventieth birthday,

his legacy nothing short of the rebirth of European culture.