A new way of looking at art was opening up, freed from history and focused on feeling and sensibility. Roberto Longhi, who “discovered” Caravaggio’s everyday drama and noted that, while sombre, Piero della Francesca’s forms were “dressed in colour”, was a great friend of the solitary Giorgio Morandi and taught in the history of art department at the University of Bologna, a department that, with Supino preceding him and Arcangeli coming after, could have easily laid claim to being one of the best in the world.

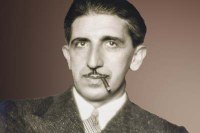

Roberto Longhi was born in Alba in 1890.

Roberto Longhi was born in Alba in 1890.

After attending the local grammar school, Regio liceo Govone, he studied at the Liceo Gioberti secondary school in Turin, earning his diploma in 1907. Remaining in the Piedmont capital, he enrolled in the Faculty of Literature, developing an interest in art thanks to his professor Pietro Toesca, student of Venturi, from whom he learned a method of studying art that involved comparing the work in question with those that preceded it and analysing its intrinsic merits.

His degree dissertation laid the practical groundwork for his future writings. In order to champion and study the work of Caravaggio more in depth, Longhi visited the various cities where the Lombard artist had worked. The result was a detailed volume that confirmed the link between Carvaggio and his followers – as Toesca taught – but also explored what Berenson had called the “tactile values” of his images, which is the say the sensory signs of colour, tone, form and movement.

He was developing a new criterion for analysis that, as Longhi himself explained in an early essay published in 1911 in “La Voce”, broke with the “historical method” formulated by Supino and Venturi.

Longhi nevertheless decided to study under Venturi at the Specialization school in Rome (1912), where he continued to contribute to Giuseppe Prezzolini’s “La Voce”.

While in Rome, he also worked towards his definition of the concept of ‘stylistic development’, writing about Tintoretto, the Genoese School and Piero della Francesca, influencing his own teacher with his innovative approach to attributing and interpreting works.

He also became critical of Berenson, after having offered to translate his fundamental volume Italian Painters of the Renaissance.

After his father died and his brother was hospitalised, Longhi began teaching in the secondary schools of Rome (one of his students was Lucia Lopresti, who later became his wife and a writer who published under the pen name Anna Banti), his lecture notes later becoming the celebrated volume Breve ma veridica storia della pittura italiana (1914).

During that same period, he wrote for the magazine “L’arte”, founded by Venturi, publishing the monographs Orazio Borgianni (1914), Battistello (1915) and Gentileschi padre e figlia (1916).

In the meantime, he also studied contemporary art, publishing the volume Scultura futurista: Boccioni in 1914 and establishing himself as a clear-eyed critic of the Italian avant-garde, while maintaining his distance, during the war, from the nationalist ideals embraced by the followers of Marinetti.

The war was also an opportunity for him to reassess Benedetto Croce’s Estetica, which he dismantled in the pamphlet Identità formale delle ‘arti belle’ od anche l’arte figurativa, arguing for the “philosophical independence of the visual language”.

In 1918, he had the fortune to meet the count Alessandro Venturi Bonaccossi, with whom he embarked upon an extended trip throughout Europe from 1920 to 1922, expanding his horizons and giving him the chance to see countless works of art first-hand.

After he returned to Rome, he began teaching at the university and contributing to “Vita Artistica”, taking over as co-editor with Emilio Cecchi in 1927. The following year, Longhi and Cecchi founded the magazine “Pinacotheca”.

His volumes Piero delle Francesca (1927) and Officina Ferrarese (1934) were a huge success, paving the way for his professorship in Medieval and Early Modern Art at the University of Bologna.

Longhi taught at the University of Bologna from 1934 to 1949 (although he only lived in the city from 1934 to 1937), and contributed to the training of not only future art historians but also famed directors and writers, who gained sophisticated knowledge of and a unique way of looking at art from his teaching: Francesco Arcangeli, Giorgio Bassani, Attilio Bertolucci, Antonio Boschetto, Alberto Graziani, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Mina Gregori and Carlo Volpe.

In addition to teaching, he organised an exhibition on 18th-century Bolognese art, the Mostra del Settecento bolognese (1935), and wrote a monograph on Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1948), turning his attention to contemporary art in the volumes Carlo Carrà (1937) and Mino Maccari (1938), but most importantly becoming close friends with Giorgio Morandi.

Moving to Florence in 1939, he co-edited the magazine “La Critica d’Arte” with Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti for two years, publishing the essay Fatti di Masolino e di Masaccio (1940), the subject of a course he taught in Bologna in 1941 that had been an aesthetic epiphany for the young Pier Paolo Pasolini.

In the meantime, World War II had begun and Longhi briefly reconnected with Croce, taking a strong position against the regime. When he refused to serve during the Republic of Salò in 1943, he was removed from teaching.

When Florence was freed, he organised an important exhibition on the work of his Bolognese friend Giorgio Morandi (1945) at the “Il Fiore” gallery, in open declaration of his wish to return to the University of Bologna.

The last courses that he held there were on Venetian painting, which he had become interested in after visiting the Cinque secoli di pittura veneta exhibition in 1945. This interest also led to the essay Viatico per i cinque secoli di pittura veneziana (1946), followed by fourteen articles published in the journal “Arte veneta” and a long-lasting collaboration with the committee of the Venice Biennale, between 1948 and 1956.

After founding the annual “Proporzioni” (which came out in 1943, 1948, 1950 and 1963), he founded the journal “Paragone” in 1950, a monthly periodical that he edited until his death and the introduction to which (Proposta per una critica d’arte) laid the foundations for the first course he held at the University of Florence, where he began teaching in 1949, after having been turned down by the University of Rome.

In 1950, he also organised an exhibition on 14th-century Bolognese painting, Mostra della pittura bolognese del Trecento, with the collaboration of young specialists including his student Francesco Arcangeli. The frescoes by Vitale da Bologna and Simone dei Crocifissi were removed from the walls of the church of Santa Apollonia for this exhibition, and are still on view today in the medieval galleries of the Pinacoteca Nazionale.

This was the beginning of a period marked by fame, collaborations and the international launch of his school of thought. Working with the critic Umberto Barbaro, he created documentaries on Carpaccio (1947), Caravaggio (1948) and Carlo Carrà (1952), but it was the 1951 exhibition in Milan, Caravaggio e i caravaggeschi, followed by a monograph on the great artist, that cemented his total success.

In Milan in 1953, Longhi organised the exhibition I pittori della realtà in Lombardia. He then worked with journals such as “L’Europeo” (1955-57) and sat on the committee for radio programmes such as “L’Approdo”, his subjects often extending to politics and social issues. His television appearances were instead rare, one being “L’approdo televisivo” in 1963.

The last exhibition that he organised was Arte lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza in 1958.

In his final years, he collected his writings for the fourteen-volume Opere complete and prepared the catalogue for his personal art collection, which he left in his will, “for the benefit of the new generations”, along with his photograph collection and immense library, in his Florentine villa in via Fortini, where the Fondazione Longhi is based today.