The University of Bologna owes much to a man who only occasionally attended its courses (and only as an auditor), never took a degree and never taught there. The major cultural reform that began in Europe at the start of the 18th century was brought to Bologna by Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, the science institute (Istituto delle Scienze) of whom was partially to thank for the return of the city and its university to the international stage.

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili was born in Bologna in 1658 to the count and countess Carlo Marsili and Margherita Hercolani.

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili was born in Bologna in 1658 to the count and countess Carlo Marsili and Margherita Hercolani.

He received a private education and, when he came of age, attended the lectures given by the physician Marcello Malpighi, the mathematician Geminiano Montanari and the botanist Lelio Trionfetti, among the few who stood out at the local university in the 17th century.

Between 1674 and 1679, his curiosity led him to travel to the major Italian cities, including Padua, where he occasionally attended mathematics courses.

He then participated in a Venetian diplomatic mission to Constantinople, where he began to study the seas and coasts, often using devices of his own invention and keeping his teachers in Bologna (Malpighi and Montanari) up-to-date with his findings. He drew on his study of coastal morphology, marine biology, the winds, the currents and salt for his first publication in 1681: Osservazioni intorno al Bosforo Tracio overo Canale di Constantinopoli rappresentate in lettera alla sacra real maestà di Cristina regina di Svezia.

In order to continue his scientific research, he decided to enlist in the Hapsburg army in 1681, which made it possible for him to travel throughout Eastern Europe, where the Hapsburg Monarchy was battling against the Ottoman Empire. In 1683, he was wounded and taken prisoner by the Tartars, who sold him to the pasha of Temesvar. Under the pasha, he distributed coffee to the Ottoman army during the siege of Vienna, an experience that allowed him to learn first-hand about the use of the substance, which was still used as a wonder drug in the west. The result was a short treatise on coffee, published in 1685: Bevanda asiatica, brindata all’em. Bonvisi, nunzio apostolico appresso la maestà dell’imperatore… che narra l’historia medica del cavè o sia caffè.

Marsili was finally freed in 1684 and, two years later, he returned to the battlefield, for the capture of Buda, where he proved indispensable for his direct knowledge of Ottoman fortifications and his tactical skills. This expedition aided his scientific research as well, and facilitated the purchase of rare books, many of which Asian codices.

He was later sent to Constantinople (1691) to sound out the possibilities for negotiations: a mission that lasted almost a full year, but came to nothing.

The Treaty of Carlowitz was finally signed in 1699, an achievement that Marsili claimed, in his autobiography, was made possible entirely through his diplomacy. His rank was in effect raised from that of assistant advisor to military general and plenipotentiary officer for the definition of the new borders. It was an arduous task, requiring him to rewrite the precarious political and geographical balances between the two continents. His research in the various places along the Danube River, chosen as the natural border, were collected in the manuscript Descrizione naturale, civile e militare delle Misie, Dacie ed Illirico, preserved at the university library in Bologna.

In 1698, Marsili published a short treatise on the nature of the light emitted by “Bologna stone”, a mineral with fluorescent properties that many had already studied (Dissertazione epistolare del fosforo minerale o sia della pietra illuminabile bolognese a’ sapienti ed eruditi signori collettori degli Acta Eruditorum di Lipsia).

Called to the front for the War of the Spanish Succession, he was given command of the fortress of Breisach, which was ruinously surrendered in 1703, leading to Marsili’s demotion and the confiscation of his assets (1704).

The defeat gave him the opportunity to devote himself more fully to his personal interests: first in Switzerland, then Milan (1704) and, finally, Cassis, in Provence, after having been received with great ceremony at the court of Louis XIV (1706).

Marsili first began thinking about founding a science institute in Bologna in 1702, wishing to bring a new experimental approach to research and education in the city, which had been languishing in provincialism for a century. That same year, he asked Eustachio Manfredi to create, in collaboration with the astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an observatory for his city palazzo, which was used three years later by the Accademia scientifica degli Inquieti, hosted in his own home. The resulting partnership led, in 1711, to the foundation of the Istituto delle Scienze, financed by Clement XI and merging the city’s science academy and its academy of fine arts (the Accademia Clementina).

The city Senate, which had been hesitant until that time to support the new cultural centre, due to its expense and risk of harming the Archiginnasio, soon found itself needing to collaborate, spurred by the pope, and, in 1712, it bought the nascent institute the 16th-century Palazzo Poggi, which was modernised and expanded and ready to relaunch Bologna’s commitment to experimentation in 1714.

That same year, he published his Dissertatio de generatione fungorum ad illustrissimum et reverendissimum praesulem Ioannem Mariam Lancisium.

The fame of his writings and, most importantly, the immediate success of his institute won him entry into the Academie des Sciences of Paris (1715) and the Royal Society of London (1722), presented at the latter by a figure no less than Isaac Newton. During his trip to England, Marsili purchased sophisticated instruments and materials for the institute, largely using funds provided by the pope.

In Bologna, tensions with the Senate remained high, with Marsili accusing the latter of not meeting its obligations with respect to the rules laid out in the institute’s Constitution in 1711 and threatening to take back the manuscripts and drawings that he had given to it. This troubled relationship left Marsili dejected and disillusioned by local politics, leading him to spend increasingly long periods in Maderno on Lake Garda and in Cassis, where he could immerse himself in his research.

His most important writings were published in Amsterdam: in 1725 the Histoire physique de la mer and in 1726 the Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus observationibus geographicis astronomicis hydrographicis historicis physicis perlustratus et in sex tomos digestus.

His quarrel with the Senate continued until 1726, when the cardinal Prospero Lambertini (the future Benedict XIV) intervened. The high prelate did not allow Marsili to transfer the institute’s presidency from the Senate to the papal legate, but he did take action to ensure that the rules were followed, such as the annual publication of the academic acts, which did not, however, start until 1731.

Unfortunately, Marsili’s wishes were never fully respected and, in 1728, weary and disillusioned, he distributed a manifesto throughout Bologna detailing what he was leaving behind, a kind of testamentary letter with which he was bidding goodbye to the city and moving back to Maderno, for the most part abandoning his family crest. He had to return to the city not long after, however, due to an illness that led to his death in 1730, although not before donating all of his manuscripts to the institute.

This generous and enlightened act, common among the great Bolognese thinkers (another example being Ulisse Aldrovandi), was summed up in Marsili’s motto: “Nihil Mihi” (Nothing to me), as we read in the museum dedicated to him in 1930 in celebration of the bicentenary of his death. The museum was created next to the vast university library that was at one time meant for the Istituto delle Scienze in Palazzo Poggi. The same building houses the numerous collections, begun by Marsili and expanded by his followers, that entered the museums of the University of Bologna.

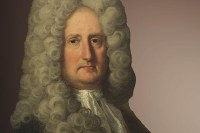

The numerous period portraits, including paintings, prints and medals, confirm the renown of this great European figure, the head of whom was displayed for the entire 18th century in the crypt of the former church of Monte Calvario and then moved to the new Certosa of Bologna in 1810. It was rediscovered by chance in 1932 and brought to the church of San Domenico, where it joined the Baroque monument to Marsili sculpted by Angelo Gabriello Piò in 1733.