Who but Carducci could have opened up the celebration of the 8th Centenary of the University of Bologna, which had called him, along with other young scholars, to bring it back to its past glories? Just as his Risorgimento poetics found the classicism of the remote past in medieval writers, so the university was entering the wider world evoking its glorious past, marked by the rediscovery of Rome’s legal texts. Two of Carducci’s missions, that of poetics and that of teaching, could therefore coincide at Bologna.

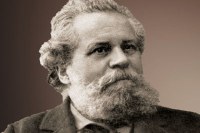

Giosuè Carducci was born in Valdicastello, in the area of Versilia, in 1835. His father, Michele, was a district doctor, fervent liberal and already an active supporter of the Italian national independence movement.

Giosuè Carducci was born in Valdicastello, in the area of Versilia, in 1835. His father, Michele, was a district doctor, fervent liberal and already an active supporter of the Italian national independence movement.

Carducci’s childhood was marked by a precarious economic situation, and, after several moves, the family finally settled in Bolgheri, on the Maremma coast, the wild, pristine landscape of which remained forever imprinted on his aesthetic sensibility.

Not being able to afford school, he was educated at home by his father and a priest by the name of Bertinelli, immediately revealing a propensity for Italian poetry and Latin.

In 1849, his family moved to Florence, where Carducci attended the Scuole Pie secondary school of the Scolopi di San Giovannino, where he became friends with his future wife, Elvira Menicucci, a relative by marriage.

These were the years that shaped the young man’s poetic inclination: patriotic and classicist, critical of the contemporary political situation.

Within the Scuole Pie, Carducci attended the Accademia dei Risoluti e Fecondi, where he caught the attention of Ranieri Sbragia, rector of the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa at the time, who convinced him to enrol in the Faculty of Literature in 1853.

The strict religious directives in force at the Scuola Normale at the time were intolerable to the anticlerical Carducci, who found his place as a contributor to the periodical Letture di famiglia, the appendix of which, l’Arpa del popolo, introduced ordinary citizens to literature, embodying D’Azeglio and Cavour’s aim to “make Italians, now that we have made Italy”.

Taking a degree in philology in 1856, Carducci’s dissertation, Della poesia cavalleresca o trovadorica, cemented the rediscovery of the classics in the literature of medieval Italian poets, the ancestors of those of the Risorgimento. The latter, while romantic, were harshly criticised by the Tuscan and his fellow intellectuals in the Amici pedanti group.

Following his graduation, Carducci turned down private teaching, choosing public education instead and moving to San Miniato al Tedesco, where he taught rhetoric at the grammar school. His initial enthusiasm soon gave way to intolerance for the location, which was isolated and narrow-minded, and his growing debt pushed him to publish his Rime in 1857.

Weary of San Miniato, Carducci returned to Florence (1857) and began a philological and literary collaboration with the publisher Gasparo Barbera. But just when things started looking up for the young man, his life was turned upside down by the suicide of his brother Dante and the death of his father (1858), after which it fell to him to support the family.

As soon as the grand duke of Tuscany was removed from power, he circulated the song A Vittorio Emanuele II, which was then transformed into the ode Alla Croce di Savoia: the resulting fame won Carducci the post of professor of Greek at the Pistoia secondary school.

In 1860, in recognition of Carducci’s dedication of the Rime to him, the minister of education Mamiani offered him a professorship in Italian eloquence (later called Italian literature) at the University of Bologna. The young professor was probably hoping for the University of Florence, but, partly to stay close to his family, he accepted the offer and held the post until 1904.

Welcomed by his colleague Emilio Teza, Carducci initially lived near Piazza Caprara. Then, when his family joined him, he moved to the modest via di Broccaindosso, where he stayed until 1876.

Mamiani’s plan was to revitalise the University of Bologna, bringing in leading lights from various disciplines (Luigi Cremona, Camillo De Meis, Pietro Ellero, G.B. Gandino, Emilio Teza, Francesco Magni, Giovanni Capellini). Although the university had been poorly run for more than two centuries, it had still been named one of the kingdom’s top schools, a distinction not bestowed upon Parma and Modena. When Carducci began teaching, however, he found himself almost without students, and lamented their preference for disciplines with more modern appeal, in a school that had very low enrolment overall (one-third of that at its competitor, the University of Pavia).

Outside the university, Carducci immediately formed a good rapport with members of Bologna’s intellectual community, meeting at the city’s cafés (Caffè Dei Grigioni in via Ugo Bassi, Caffè dei Cacciatori in what was once via del Mercato di Mezzo, Caffè del Pavaglione, near the university’s old premises), and joined and founded numerous democratic and pro-Garibaldi masonic lodges.

His enthusiasm for scientific progress and fascination with nature, demeaned for millennia by Church morality, inspired his famed hymn A Satana (1863).

The years that followed were, in general, full of frustrations: the failure of Garibaldi’s march on Rome (1862), the lacklustre reception of the collection Levia Gravia (1868) and constant arguing with colleagues and fellow Masons.

Although he had deliberately avoided political texts in Levia Gravia, which he had also published under the pseudonym Enotrio Romano, in 1869 he unleashed his writings against Pius IX and celebrated the heroism of Giovanni Cairoli and Ugo Bassi (he dedicated one sonnet to the naming of a main street in Bologna after the Barnabite friar).

His republican and democratic leanings also came to the fore in his participation at the meeting organised at the Teatro Comunale by the professor of penal law Pietro Ellero against the death penalty and then at the Congresso di mutuo soccorso (1880), where he forcefully defended the principles of universal suffrage.

In the meantime, in 1865, Carducci had been appointed secretary of the Regia Deputazione di Storia Patria, an association devoted to the medieval history of the Romagna provinces (he became its president in 1887).

In 1867, he began a collaboration with the Zanichelli bookshop, where his “coterie” met.

The same year, he supported the launch of Enrico Panzacchi’s ‘Rivista bolognese’ and published his first Giambi ed Epodi in the republican newspaper “L’amico del popolo” (the offices of which were in Palazzo Paleotti, in via Zamboni, now a university building)

In 1868, he was removed from teaching for having celebrated the anniversary of the Roman Republic, but this only made him more of a hero in the students’ eyes.

The following year, he and other democratic academics sat on the Casarini town council.

He was devastated by the deaths of his beloved mother and his son Dante, both in 1870, and he struggled to recover, aided in part by the success of the anthological publication of his poetry, a project championed by Barbera and divided into Decennali (1860-70), Levia Gravia (1857-70) and Juvenilia (1850-57), followed in 1873 by Nuove Poesie, which, although stirring quick reactions for their strong political condemnation, were a widespread success in Italy and abroad, winning him international fame.

This did not, however, distract Carducci from his educational mission, and in 1871 he became president of the nascent Lega per l’istruzione del popolo (league for the education of the people), in a city where 47% of the population was illiterate at the time. The city helped mitigate this situation by offering scholarships for the Faculty of Literature, one of which was won by Giovanni Pascoli (in 1866, Carducci had had just one student, whereas in the years that followed he managed to have barely five). The professor knew that cultural deterioration could only be overcome by giving women access to education (his student Giulia Cavallari Cantalamessa was the first in Italy to take a degree in literature and philosophy). Towards this end, the transformation of the teacher training school into a faculty (1876) was of fundamental importance, contributing to the university enrolment of an unprecedented number of women. Carducci served as head of the humanities department until 1896. In the interest of making a concrete difference, he began contributing in 1900 to the periodical Strenna universitaria, which collected funds for less well-off students.

Rich, famous and satisfied, Carducci moved to the more respectable Palazzo Rizzoli, in Strada Maggiore, in 1876, remaining there until 1890.

That same year, he was elected member of parliament for the district of Lugo di Romagna, a largely honorific post.

He also began the Odi barbare. In 1877, he published the fourteen odes to the immensity of nature and wisdom of history. Political wrath and social criticism had given way to a search for beauty.

The odes were misunderstood, especially by the public, but the criticism did not distract Carducci from his newest passion: Carolina Cristofori Piva, who appears in his works as Lina and Lidia.

The other woman who captured the poet’s imagination was Margaret of Savoy, queen of Italy. Arriving in Bologna with her husband Umberto I in 1878, the poet was seduced by her presence and harshly criticised by his fellow republicans as a result. He belatedly tried to justify himself in the article Eterno feminino regale (1882), in which he declared himself a follower of love for his country and not a political ideal. This was, however, the beginning of his growing support for the monarchy.

His stays in Rome became longer and more frequent, during which the poet could breathe in the classicism that he had held in his heart since adolescence. In the capital, he met Angelo Sommaruga, who persuaded him to contribute to his successful new literary magazine – in truth, more interested in gossip than criticism – Cronaca Bizantina, the first issue of which was came out in 1881.

The same year, the poet was made a member of the Consiglio Superiore dell’Istruzione.

For Carducci, the 1880s were a time of new editions and new publications (Juvenilia, Nuove Odi barbare, Giambi ed Epodi, Rime Nuove, Terze Odi barbare and Opere).

In 1886, after years of absence, he was re-elected to the town council and helped win approval of the celebratory date of the 8th Centenary of the University of Bologna, a date arbitrarily suggested by the young Corrado Ricci and supported by Carducci and Cesare Albicini. Thus began the complex organisation of the university’s relaunch, thanks to the university committee conceived by the jurist Giuseppe Ceneri and presided over by the rector Giovanni Capellini.

On 12 June 1888, at the freshly-scrubbed university and in the presence of the king and queen, Carducci sang the praises of the oldest university of the west (his famous speech was immediately published by Zanichelli).

In the wake of this celebration, he triumphed the following year in the city elections, on the party list of the liberal democrats.

1889 was also the year in which he became president of the Commissione per i Testi di Lingua, a cultural association devoted to tracing and making known 14th- and 15th-century Italian writers (a post he held until his death).

In 1890, he moved to his new home in via del Piombo, now Piazza Carducci, where he remained until the end of his days.

That same year, he was named senator and passionately supported the conservative politics of Francesco Crispi (in reality, he only spoke out three times, the first in 1892, to defend the importance of secondary-school teaching)

His positions distanced him from his students, who attacked him in 1891 for having attended the inauguration of the Circolo Liberale Monarchico Universitario and, in 1895, for having supported the African campaigns.

Nevertheless, when he celebrated his thirty-five years of teaching in 1896, he was treated with affection and appreciation and given honorary citizenship, in part for having turned down the Dante professorship in Rome in 1887.

His last literary effort was published in 1898: Rime e Ritmi.

Finally, he was an enthusiastic, active participant in projects for urban redevelopment, for which the Comitato per Bologna Storica Artistica, of which he became an honorary member in 1901, played a critical role in decision-making. These were the years of the city’s first town plan (1889-1899), which also involved the expansion and modernisation of the university. In a speech delivered to the Senate in 1899, Carducci complained about the inadequacy and precariousness of the university’s facilities, which had seen enrolment increase from 400 students in the 1860s to more than four times that at the end of the century.

The small classroom where he gave lectures was not, however, touched, and can be visited today in the university’s Palazzo Poggi.

When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1906, he had been sick for quite some time and confined to his home, which is where he received the coveted award.

His professorship was given that same year to Giovanni Pascoli, following the suicide of Carducci’s student and designated successor, Severino Ferrari.

A few months later, Carducci himself died, in 1907, in the house that was then purchased by Queen Margaret, passed to the city, which preserved its original objects and furnishings and important library, and, finally, became home to the Museo del Risorgimento (1990). The best possible place, for the bard of liberation and the Italian tradition (indeed, in 1893, Carducci joined the committee for the creation of a museum for the collection of relics of the Risorgimento).

A large monument by Leonardo Bistolfi (1908-28) stands in the piazza dedicated to Carducci next to the house museum. The marble poet is still there, thoughtful and absorbed between his two life companions: Nature and Poetry.